Frances Robinson AssocFCGDent, Advanced Oral Health Practitioner and Chair of the Board of the Faculty of Dental Hygiene & Dental Therapy, reflects on The Dental Health Barometer report on preventative oral healthcare, published by the College and Haleon.

The Dental Health Barometer report, stemming from a collaboration between the College of General Dentistry and Haleon, surveyed patients and dental professionals and more recently held focus groups with dental professionals throughout the UK. The report highlights inconsistencies in the provision of preventative oral healthcare and how this type of care is understood by both the dental population and the wider public.

Due to my roles as an Advanced Oral Health Practitioner in London and as Chair of the Board in the College’s Faculty of Dental Hygiene & Dental Therapy, this piece of research with Haleon, was particularly interesting to me. I currently lead a mixed team of dental professionals and admin support to provide an oral health promotion service, through an NHS trust, contracted by the local authority. In my borough the decay rate was 39.1% for five-years olds in 2019 – I have much work to do!

I can sense clinicians are frustrated when working at the coal face of primary care seeing so much decay and periodontal issues, but dental outreach teams, like mine, and the dental public health workforce, work tirelessly to address some of the points raised by clinicians in the report.

I would like to use this blog piece to highlight some of the key summary points raised in the CGDent-Haleon report that are directly related to my role and also to explain some of the work that goes on in oral health outreach teams.

What is the current picture of oral health?

23.4% of children in England had tooth decay in 2019, normally with three to four teeth affected (National Epidemiology Survey for England). Furthermore, tooth decay still persists and is the top reason for five to nine year old children to be admitted to hospital and given a general anaesthetic. In 2022, the prevalence of the tooth decay in more deprived areas was 35% compared to 13.5% in the most affluent.

For adults, the last adult oral health survey showed 41% of people in deprived neighbourhoods had dental pain, compared with 25% of those in the least deprived neighbourhoods. Furthermore, 84% of adults fall into groups that put them at higher risk of the disease i.e. high sugar diet and infrequent dental attenders.

Tooth decay is preventable and inequalities are unfair, yet avoidable. Preventative dental care is proactively helping a patient to take action to maintain a healthy mouth, however, as the CGDent-Haleon report highlights, both the ability to provide preventative advice and the consistency of the advice given varies between professionals.

Greater provision of CPD

In clinical practice, clinicians are used to treating patients to a high standard according to the best available evidence base. This may be using the best materials and the selection of treatment options on a case-by-case basis. ‘The Dental Health Barometer‘ seems to demonstrate that current understanding of evidence-based population dental approaches varies in primary dental workforces. Dental public health is taught on undergraduate curriculums but clinicians may be unaware of recent updates to evidence bases. Subsequently, in order to use the primary dental health workforce to contribute to improving oral health outside the dental surgery, it is pertinent to ensure the evidence base is widely understood. There is a risk that some oral health approaches and interventions, although well intentioned, are either at best ineffective or at worst could widen oral health inequalities.

Indeed, the report calls for “greater provision of CPD on the delivery of preventative care”, in this instance it would be a good opportunity for this type of CPD to also cover community based oral health approaches, as well as those more applicable to clinical settings.

Evidence based public health dentistry

Currently, it seems many well-intentioned efforts to improve oral health on a population level don’t actually align to the current evidence base. Giving oral health ‘education’ in the form of assemblies, class room talks or at health fairs, is not proven to improve oral health outcomes. The ‘commissioning for oral health‘ document highlights that for school aged children, one-off dental health education is ineffective and therefore discouraged.

These traditional oral health approaches that focus solely on education can actually widen oral health inequalities in deprived areas. A one-off oral health session only gives knowledge to those with the means i.e. financial and social resources to act on advice, but for vulnerable families it doesn’t empower them to make sustainable change. They might want to go home and buy toothbrushes and toothpastes and healthy food for their family, but they may also have to consider the family budget, constraints on the family’s time and other social factors. Furthermore, sustained behaviour change is seldom achieved in one visit, it takes time and patience to build daily oral health habits as we know from our work on a one-to-one level with patients in clinics.

In my role as an Advanced Oral Health Practitioner, I have heard of families all using the same toothbrush because they cannot afford to buy ones for each family member, and I have met families living in temporary accommodation with limited access to cooking facilities and personal hygiene spaces. These families living in deprivation as highlighted are more likely to be the ones suffering from poor oral health.

The Association of Directors of Public Health stated in 2023, “worrying oral health findings are not a result of behaviour, poor choices or a lack of education.” But rather research, conducted by Public Health England, has called for “action to tackle the underlying causes of health inequalities. Creating healthier public policies, supportive environments and strengthening community action, to improve oral health.”

Indeed, Professor Sir Michael Marmott poses the question on the first page of his book ‘The Health Gap‘, “why treat people only to send people back to the conditions that made them sick in the first place?”.

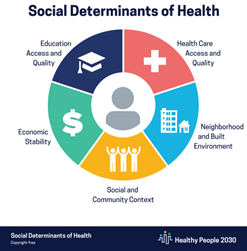

On a population level, the conditions in which each family lives has a bigger influence on their health outcomes than individual decisions. Research has shown that the social determinants of health account for 30-55% of someone’s health outcomes. Subsequently programmes that consider the social determinants of health, (the conditions in which children and adults can live, grow, work and age) have the best evidence-base behind them.

There is strong supportive evidence for supervised toothbrushing programmes and fluoride varnish programmes, which were mentioned in the CGDent-Haleon report. Also dental professionals suggested collaboration and oral health training for the wider professional workforce (health, education, social). This is further encouraged by the commissioning for better oral health document, as they build on existing capacity and can be targeted to high risk groups.

Why is there variation between which oral health prevention services are offered in different areas?

Oral health is designated to local authority level and subsequently there are huge variations in what is offered on a national scale. This can be confusing for dental professionals working in primary care and the public, which is shown by the recent report.

Within London, I am aware of every borough having a different approach to commissioned oral health programmes and this can result in a postcode lottery in terms of what is provided. The borough I work in has fluoride varnish programmes and supervised toothbrushing programmes in a certain proportion of targeted schools and all SEN schools. But we also provide comprehensive training for health, social and educational professionals for oral health – aligning to the evidence base around capacity building on existing services. This includes working with care homes, carers, outreach workers, social workers, health visitors, nursery staff and recruiting ‘Oral Health Champions’ in all settings we work with. This approach may not be replicated across the UK and dental professionals in primary care may not be aware of the current commissioning of an oral health team in their area.

Indeed, there are calls in the CGDent-Haleon report for a national oral health programme (similar to ChildSmile in Scotland or Designed to Smile in Wales) which creates a base level of preventative care, for both children and adults and integrates oral health into general health. It could use universal proportionalism to scale up priorities, identified by local need. If there was a national oral health programme there could be potential for local practices to assist with the running of this, for example training teachers on supervised tooth brushing programmes or visiting local care homes to provide quality assured oral health training to staff members.

Oral health was included in a recent NHS England initiative Core20PLUS5, a national NHS England approach to support the reduction of health inequalities at both national and system level. The approach defines a target population cohort of the most deprived 20%, plus inclusion health groups and identifies ‘5’ focus clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement. The Core20PLUS5 for children did include oral health as a priority so there is hope that some of our concerns as professionals are being heard on a wider level, and taken alongside the recent publication of the ‘The Dental Health Barometer’ report by the College and Haleon, there may be hope for the future!